The Australian Privacy Foundation (APF) has called out the federal government and the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC) after failing to publish a report on the September 2016 incident that revealed Medicare Benefits Schedule and Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme data was not encrypted properly.

The dataset was found by a team of researchers from the University of Melbourne and was subsequently pulled down by the Department of Health.

At the time, the OAIC announced it was investigating the publication of the datasets, however more than 12 months later, it is still investigating.

Of concern to the APF is that there has been no public report, nor warning about the bug in open data; no indication of when the report will be released; and no requirement to reconsider the misplaced trust in the de-identification of open data.

"You should be able to trust governments to care for sensitive personal data about yourself and your family. Clearly some of those who are handling this data either lack expertise, or are careless: It appears that 'Open Data' protections can be breached," a statement from the APF reads.

While the APF agrees there can be benefits from the sharing of health and other personal information among health care professionals and researchers, it said the sharing must be based on an understanding of potential risks.

"It must only occur within an effective legal framework, and controls appropriate for those risks," the APF continued.

"A 'Trust me, I'm from the government!' approach is a recipe for pain. So is sharing such sensitive data with government without full openness, transparency, and a legal framework that prevents them from misusing it out of the public eye."

The research team that re-identified the data in September 2016, consisting of Dr Chris Culnane, Dr Benjamin Rubinstein, and Dr Vanessa Teague, reported in December further information such as medical billing records of one-tenth of all Australians -- approximately 2.9 million people -- were potentially re-identifiable in the same dataset.

"We found that patients can be re-identified, without decryption, through a process of linking the unencrypted parts of the record with known information about the individual such as medical procedures and year of birth," Dr Culnane said.

"This shows the surprising ease with which de-identification can fail, highlighting the risky balance between data sharing and privacy."

The team warned that they expect similar results with other data held by the government, such as Census data, tax records, mental health records, penal data, and Centrelink data.

The large-scale dataset relating to the health of many Australians, under what the APF labelled as "the fashionable rubric of open data", included all publicly reimbursed medical and pharmaceutical bills for selected patients spanning the thirty years from 1984 to 2014. The data as released was meant to be de-identified, meaning that it supposedly could not be linked to a particular individual.

"Unfortunately, the government got it wrong: This weak protection can be breached," the APF added.

See also: Australian Privacy Foundation wants 'privacy tort' to protect health data

The Privacy Foundation believes the Department of Health and its minister should be held to account for the data being re-identifiable, as well as the OAIC, with APF expanding on its previous claims the agency led by Timothy Pilgrim was being "underfed".

"The OAIC should act like a watchdog, not like a rather timid snail," the APF said on Monday, hoping the appointment of a new Attorney-General after George Brandis was replaced by former Minister for Social Services Christian Porter in December will "provide adequate resources" to the agency.

As a result of the issues found by the University of Melbourne, in October 2016, the Australian government proposed changes to the Privacy Act 1988 that would criminalise the intentional re-identification and disclosure of de-identified Commonwealth datasets, reverse the onus of proof, and be retrospectively applied from September 29, 2016.

Under the changes, anyone who intentionally re-identifies a de-identified dataset from a federal agency could face two years' imprisonment, unless they work in a university or other state government body, or have a contract with the federal government that allows such work to be conducted.

The university team said the proposed legislation will have a chilling effect on research, and risks efforts to make sure open data is properly protected.

"Whilst open data is not a safe approach for releasing this type of data, open government is the right paradigm for deciding what is," the team said. "One thing is certain: Open publication of de-identified data is not a secure solution for sensitive unit-record level data."

Speaking a few months after the first batch of information was re-identified, Pilgrim said building trust with the public is key to the challenges big data presents for organisations, including government, and highlighted that trust is further challenged by the nature of secondary uses of data.

"Part of the solution, potentially a significant part I suggest, lies in getting de-identification right," he said during a data sharing and interoperability workshop at the GovInnovate summit in Canberra late 2016.

"This includes ensuring that government agencies, regulators, businesses, and technology professionals have a common understanding as to what 'getting it right' means.

"At the moment, that common clarity is not evident."

While Pilgrim said that de-identification can be a smart and contemporary response to the privacy challenges of big data, which he said aims to separate the "personal" from the "information" within data sets, the commissioner highlighted that there was no clear-cut definition of how far-removed personal identifiers needed to be before the dataset is considered de-identified.

"I stress as privacy commissioner that de-identification is not the only approach available to manage the privacy dimensions of big data, but we are keen to explore its potential when done fully and correctly," he said.

"That potential could include the ability to facilitate data sharing between agencies, and unlock policy and service gains of big data innovation, whilst protecting the fundamental human right to privacy.

"That is a great prospect, and one worth pursuing."

See also: OAIC and Data61 offer up data de-identification framework

Given the investigation into the MBS and PBS datasets is ongoing, the OAIC said on Monday it is unable to comment on it further at this time.

"The commissioner will make a public statement at the conclusion of the investigation," a statement from the OAIC reads.

"The OAIC continues to work with Australian Government agencies to enhance privacy protection in published datasets."

From:http://www.zdnet.com/article/privacy-foundation-trusting-government-with-open-data-a-recipe-for-pain/

About OsMonitor:

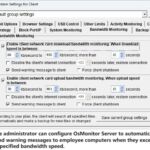

The mission of OsMonitor is to create a Windows computer system tailored for work purposes, effectively regulating employee computer behavior. It enables employers to understand what employees are doing each day, monitoring every action, including screen activity and internet usage. Additionally, it restricts employees from engaging in specific activities such as online shopping, gaming, and the use of USB drives.

OsMonitor, designed purely as software, is remarkably user-friendly and requires no additional hardware modifications. A single management machine can oversee all employee computers. As a leading brand in employee computer monitoring software with over a decade of successful operation, OsMonitor has rapidly captured the global market with its minimal file size and excellent cost-effectiveness compared to similar software. At this moment, thousands of business computers worldwide are running OsMonitor daily.